It’s been a while since I’ve written about my music, and I’ve built up quite a backlog. I make music that is just as obstinately original and out-there as the opinions I cultivate, because the conventional music of this culture is just as dead as the ideas it was founded upon. I make my own music because I want to hear something that I only hear bits of in other people’s music, and I like music that challenges the listener, and traditional musical ideas. I’m not interested in preserving musical traditions, I want to make music for a very different future.

Still, I am a product of my time, and when I was young and the future looked bright, synthesizers were brand new and seemed to me like almost magical devices. Back then, I liked what Edgar Froese, Morton Subotnik, and Klaus Schulz did with them much more than I liked what Walter Carlos, Kieth Emerson or Patrick Moraz did with them. I liked the people who explored synthesizers on their own terms, terms like millisecond and frequency, rather than those who played more or less traditional piano music on these new instruments. I still enjoy that early psychedelic electronic space music and you can hear that influence in a lot of my music.

Tom Robbins reminds us that “It’s never too late to have a happy childhood.” so I recently did something I’ve wanted to do since I was 15. A couple of years ago I created the GeoSafari Modular Analog Synthesizer, a crude but unique electronic musical instrument that I built from scratch. I’m sure I told you about it.

When I was 15, I was in my first extra-curricular musical project with some of my friends from school. We called ourselves, “Raw Sewage” and we sounded almost as good as our name. Two of my band-mates in this ensemble built their own synthesizers. At the time, I was not at all impressed by these machines. They didn’t look anything like musical instruments. They looked like something a 15 year old would build in his dad’s workshop, out of scrap wood. They had loose wires dangling from them, and looked like they could fall apart at any moment, but the thing that made me most skeptical of these machines was that they were powered by a 9 volt battery.

Back then, I knew that all “real” rock-n-roll gear plugged into the wall and weighed a lot, and these machines did neither. They sounded terrible too. The machines seemed to be very unpredictable, and even the guys who built them, couldn’t figure out how to make them work most of the time. When the machines did make noise, they seemed as surprised as the rest of us by the noises they produced, and none of them sounded very good.

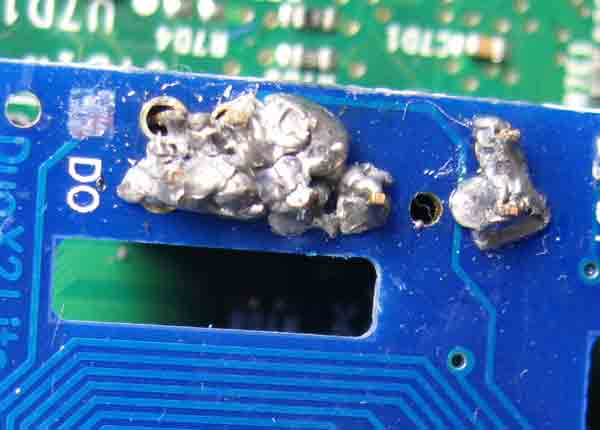

Still, as a teenager, I had friends who built their own synthesizers, and shared their PAIA catalogs with me, catalogs full of synthesizer kits you could build at home. I thought it would be a cool thing to do, but my own early attempts at soldering did not go well, so I focused on other things. Before long, I met someone who had a “real” Moog synthesizer and discovered that it sounded almost as ugly as the machines my friends had built.

Eventually, I bought a Roland SH-09 monophonic analog synthesizer for myself. I figured out how it worked, and learned to play it. I discovered that synthesizers really need reverb to sound good. The reason synthesizer music sounds so spacey has as much to do with the artificial acoustics added to them, as it does with the signals the instruments produce. Ironically, I got rid of my Roland when I went off-grid, because it required AC power, while everything else I now use runs on 9 volts DC.

Years later, however, when I decided I wanted a new synthesizer, and I needed one that could run on 9 volts DC, I knew I could build it myself because if Phil Casey and Andy Izold could do it, when they were 15, I could do it too. So, a couple of years ago I built the thing, and for the last couple of years I’ve been exploring its musical potential. Today, I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of what it can do, but I know that a lot of what it can do is sound really awful.

Once in a while, however, it sounds pretty good, at least to my ears, and lately I’ve been getting a little better at it. I have assembled a collection of some of my favorite electronic realizations from the GeoSafari Modular Analog into a new album. I call the album “Vintage Star Traveler” because it reminds me of the golden age of science fiction. It reminds me of a quaint, optimistic vision of rocket-ships and space stations, and technology without limits.

I don’t hold out much hope for such a future, or even think it’s a good idea, but I do feel nostalgic for that time in the past when it seemed possible. Primitive analog synthesizers helped conjure those visions of the future, and fueled the idea that technology would change everything. Now that technology has changed everything, the GeoSafari Modular Analog takes me back to a time before we knew how badly it was all going to go.

I made a video to go with the title track from the album. To create the images for this video, I recycled some old video feedback and experimental footage I shot back in the ’90s when I did more video work. I like the way it came out. The video has a rather retro psychedelic look about it that, I think, matches the music. Please check it out.

The album contains more than 58 minutes of dreamy, futuristic soundscapes created with the GeoSafari Modular Analog Synthesizer. I find the whole album quite relaxing and energizing, and I like the way my brain feels when I listen to it. I hope it does the same for you. You can listen to the whole album and download it for free here:

You can listen to all of my music, download it for free, and learn more about it at: www.electricearthmusic.wordpress.com