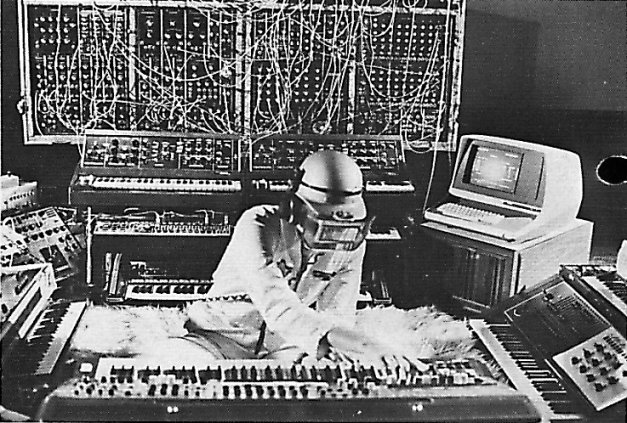

I bought this old Casiotone CT-360 keyboard at a yard sale in Garberville, for $5, with the express purpose of bending it. That is, hacking the circuit-board to exploit whatever glitches, distortion and weirdness I could coax out of it. So, the first thing I did when I got it home was take the back off of it, exposing the circuit-board, turned it on, and started one of those cheesy rhythms playing while I probed the circuit. All weekend I kept playing those incessant mechanical rhythms. I even put a block of wood under one of the keys, so notes kept bleating for hours. I found quite a few interesting short-circuits on the board, but the noise almost drove me crazy.

As those canned rhythms churned on and on and random notes screamed away for hours on end, the internal speaker impressed me with its brightness, and overall volume. In other words, it was F-ing loud. The speaker made bending convenient, but I didn’t imagine I would use it much, since I usually plug electronic instruments directly into a mixer or recorder, and listen to it on my studio monitors. In fact, when I needed a place to mount the knobs and switches that trigger the glitches and malfunctions I found on the circuit-board, the speaker grill, located directly to the left of the keys seemed the perfect location.

I removed the speaker, cut a hole in the speaker grill, and mounted all of the switches and knobs on a wooden disc I recycled from a round box that originally contained a small wheel of goat-milk brie cheese. It fit perfectly. I added a quarter-inch phone jack, and a switch that allows you to turn the internal speaker, a smaller, quieter speaker that I added, and placed elsewhere in the device. When I finally put the whole thing back together, it all malfunctioned perfectly.

But I had this speaker left over, this loud, bright, 3W 4Ohm 5” Samsung driver. Then I had an idea. It wasn’t an original idea, and it wasn’t the first time I’d thought of it, but clearly its time had come. Joe Walsh and Bob Heil put this idea in my head a long time ago with the guitar solo to “Rocky Mountain Way.” I loved that song when I was a kid. Heil and Walsh worked together to build a device that works on this principle for the vocalized guitar solo in that song. Heil went into production with the device, dubbing it the “Talk Box” and gave one of the very first production models to Peter Frampton who famously used it on “Do You Feel Like We Do?” David Guilmore used one on “Pigs” on the Pink Floyd album “Animals” and many other artists found use for this device as well.

I believe Heil still makes some version of the Talk Box. Craig Anderton, in his book “Electronic Projects for Musicians” tells you how to build something like Heil’s Talk Box, but he recommends using the driver from a horn speaker, so his design requires no funnel. However, I once interviewed Bob Heil for my radio show, and I asked him about the Talk Box and how they created that sound. In that interview, Bob Heil told me that they set out to recreate an old blues trick of putting a funnel with a piece of hose attached to it, over the speaker of a guitar amplifier. By putting the other end of the hose in his mouth, a player could appear to “sing” guitar notes by silently moving his mouth.

None of the modern designs for this kind of effect use a funnel with a conventional paper cone driver. Instead, they all use a more specialized driver, but I knew about the funnel from talking to Bob Heil, and it works well. I’m sure it helps that it is such a loud and bright little speaker, and such a loud and bright little synthesizer. They work marvelously together, but the device will work with any audio source loud enough to drive the speaker without burning it out. I really love the way this device allows you to sculpt sound, turning relatively flat electronic signals into full bodied musical expressions. I’m completely hooked on it and I expect to use it quite a bit in the future. I’m sure a lot of musicians would have use for a device like this, and I hope this encourages some of them to build one for themselves.